Paul Silas who was 3-time NBA champion player and coach has died at the age of 79 on 11th December 2022.

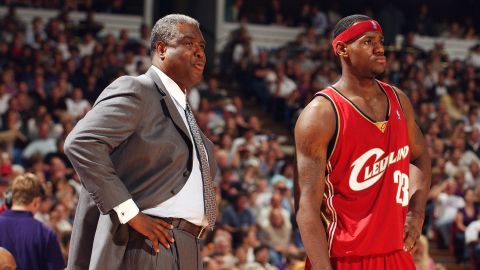

Paul Silas, a rebounding and defensive pillar on three N.B.A. championship teams, who went on to a coaching career that included presiding over LeBron James’s professional debut with the Cleveland Cavaliers, died on Saturday at his home in Denver, N.C., outside Charlotte. He was 79.

What was the cause of Paul Silas Death?

The death cause of Paul Silas was cardiac arrest according to his daughter Paula Silas-Guy said.

Full Biography of Paul Silas

Silas was known for his tactical approach to rebounding, especially on offense. A robust 6-foot-7-inch forward, he studied the arc and spin of his teammates’ shots to compensate for his lack of vertical skills.

Paul Theron Silas (born July 12, 1943) is a former NBA head coach and retired American professional basketball player. In 1963, he averaged 20.6 rebounds per game while at Creighton University, where he set an NCAA record for most rebounds in three seasons.

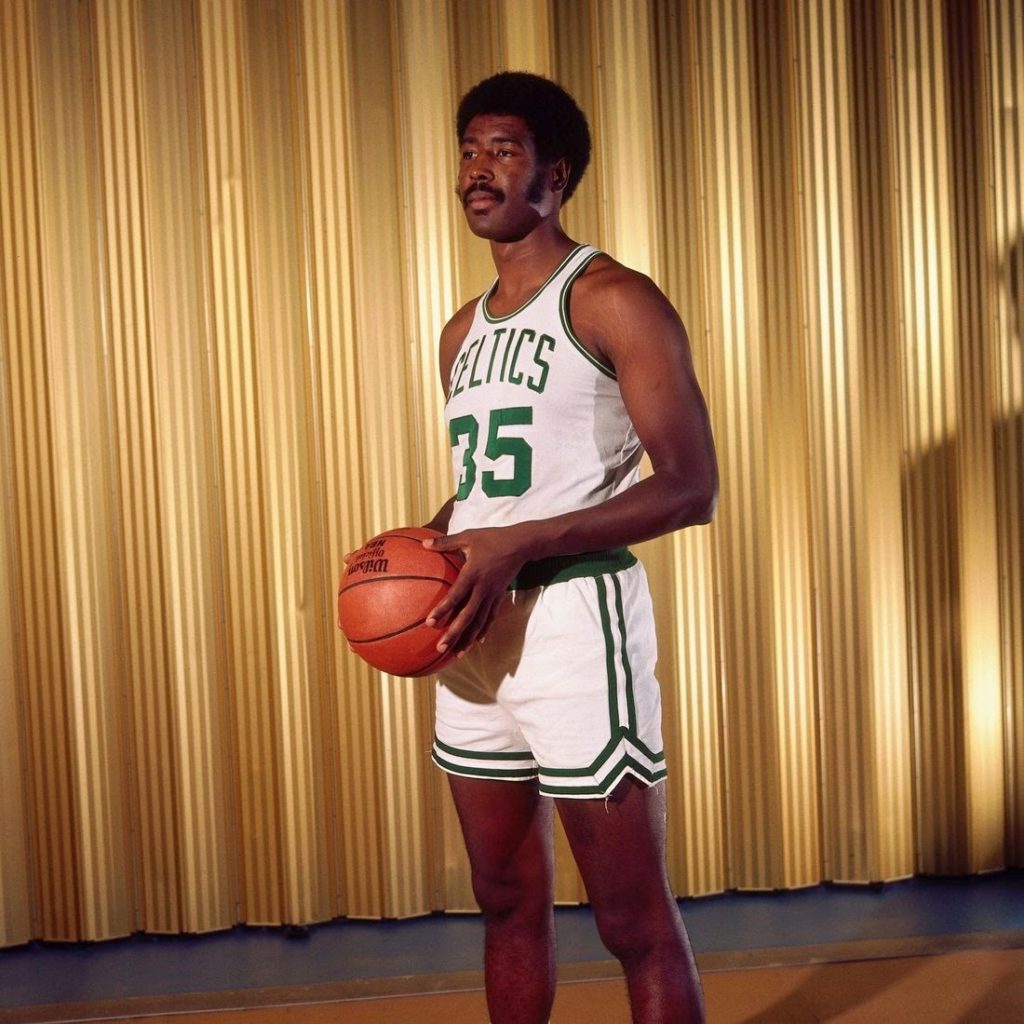

During his 16-year NBA career, Silas amassed over 10,000 points and 10,000 rebounds, appeared in two All-Star games, and won three championship rings (two with the Boston Celtics in 1974 and 1976, and one with the Seattle SuperSonics in 1979). He was twice named to the All-NBA Defensive First Team and three times to the All-NBA Defensive Second Team.

Related News: Sacramento Kings Vs Utah Jazz NBA Highlights, News, Score, Draft and injury

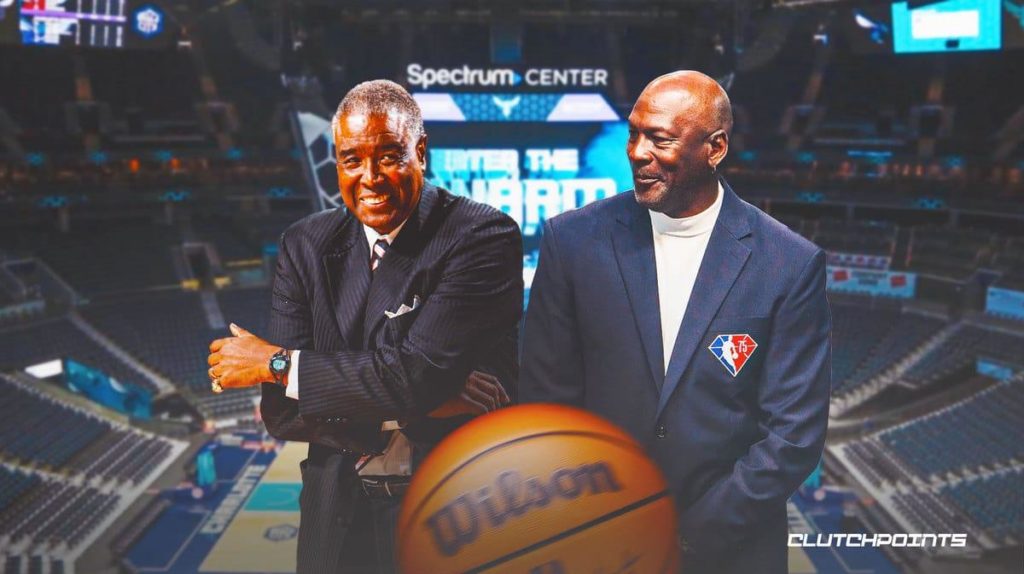

He was the Cleveland Cavaliers’ head coach until March 21, 2005. Prior to joining the Cavaliers, he was the head coach of the San Diego Clippers and the Charlotte/New Orleans Hornets. He worked for ESPN, but he interviewed for the vacant head coaching position with the Charlotte Bobcats in April 2007, which was eventually filled by Sam Vincent.

After being fired in April 2008, Sam Vincent stated that coaching the Bobcats would be a “dream job.” Paul Silas was named interim head coach of the Bobcats on December 22, 2010, succeeding outgoing coach Larry Brown. The Bobcats removed his interim status on February 16, 2011. The Bobcats announced on April 30, 2012, that Silas would not be returning for the 2012-2013 season.

Paul Silas, former NBA defensive player and head coach, died at the age of 79.

He played for the Celtics for 16 seasons and was known for his rebounding. He was also LeBron James’ first professional coach.

Paul Silas, a rebounding and defensive pillar on three NBA championship teams who went on to coach LeBron James’ professional debut with the Cleveland Cavaliers, died on Saturday at his home in Denver, N.C., outside Charlotte. He was 79.

According to his daughter Paula Silas-Guy, the cause was cardiac arrest.

Silas was well-known for his strategic approach to rebounding, particularly on offense. To compensate for his lack of vertical skills, the 6-foot-7-inch forward studied the arc and spin of his teammates’ shots.

“I used to tell him that you couldn’t slip a sheet of paper under his feet, but he was still an incredible rebounder,” Lenny Wilkens, Silas’s teammate with the St. Louis Hawks when he entered the NBA in 1964, said earlier this year in an interview for this obituary. “Once he was in place, you couldn’t move him.”

Silas played for five NBA teams, the last of which was the Seattle SuperSonics, where he reunited with Wilkens, who coached the team, and became a valuable role player during the team’s championship season in 1978-79.

In 1975, Silas shoots against the Houston Rockets. He was most prominent when he was with the Celtics, where he formed a tough frontcourt tandem with Dave Cowens.

Read More..

But it was with the Boston Celtics, after five years with the Hawks and three in Phoenix, that Silas had his most successful season. Silas was acquired from the Suns in 1972 by Celtics patriarch Red Auerbach in exchange for Charlie Scott’s negotiating rights. He formed a tough frontcourt tandem with Dave Cowens, a 6-foot-9 center.

Silas was pursued by Auerbach after he had his best statistical season, averaging 17.5 points and 11.9 rebounds. “The main reason Red wanted Silas was to deal with Dave DeBusschere, who had been wearing them out,” said Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe, referring to the rival Knicks’ star forward.

Cowens and Silas developed an on-court chemistry quickly, with Cowens’ ability to shoot from the perimeter opening up the interior for Silas to outmuscle opponents around the basket, where he also had a deft tiptoe push shot.

“Me and Dave started just wearing teams out,” Silas told Grantland, a sports digital publication, in 2014. “By that I mean wear them out.”

The Celtics, led by Tom Heinsohn, used Silas as a starter and in the role made famous by his teammate John Havlicek, as the first sub off the bench, or sixth man.

They avenged a 1973 loss to the Knicks in the Eastern Conference finals, then outlasted the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar-led Milwaukee Bucks in the league finals, winning the final game on the road.

The Celtics won the 1976 championship with a core of Cowens, Havlicek, Jo Jo White, Silas, and Scott, whose rights were reacquired by Auerbach in 1975.

After a salary dispute, Auerbach made what The Globe’s Ryan called “his greatest blunder,” trading Silas to the Denver Nuggets. Aligned with Larry Fleisher, the NBA Players’ Association’s executive director and the sport’s most powerful agent, Silas insisted on being paid like the Celtics’ stars — especially the team’s white stars.

Silas discovered that black players were paid less than white players of similar, and sometimes inferior, ability, thanks to Fleisher’s assistance and some locker room sleuthing.

According to Don Chaney, another Black Celtic who left the team in 1975 for more money in the rival American Basketball Association, Auerbach would tell players during negotiations, “I’m giving you this, don’t tell anyone else.”

“No one ever spoke until Silas came along,” Chaney said in 1991. “He began approaching men and asking, ‘What are you making?'”

Related News: Brazilian soccer legend Pelé dies at 82

Silas’ departure precipitated the Celtics’ decline in the late 1970s, prompting Cowens to take a two-month sabbatical at the start of the 1976-77 season.

“We’d just won the championship in 1976, so it was like, why mess with a good thing?” Cowens stated in a Grantland article in 2014. “I was irritated with everyone.” I was angry at Paul and the Celtics for allowing this to happen.”

Silas with the Denver Nuggets in 1977.

Silas expressed regret about leaving the Celtics when his playing time in Denver decreased. He was looking forward to seeing Wilkens, the star guard who had inspired the young Silas to lose 30 pounds and play at 220 pounds in St. Louis.

“I’d force him to play me one-on-one,” Wilkens said. “Paul enjoyed eating, and I used to tell him, ‘You’ll never be able to guard me unless you get on that diet,’ which he did.”

Paul Theron Silas was born on July 12, 1943, in Prescott, Arkansas, and moved to Oakland, California, when he was eight years old, with his parents, Leon and Clara, and two brothers. His father was a railway porter. The family initially shared a home in Oakland with Silas’ cousins, three of whom went on to form the rhythm and blues group the Pointer Sisters.

Also Read; Derrick Henry hits Jaguars’ Rayshawn Jenkins with brutal stiff arm in AFC South title game.

Silas sang in the school choir with his cousins, but he spent most of his free time at West Oakland’s DeFremery Park, watching and idolizing future Celtics great Bill Russell dominate the competition. Silas led the varsity to a 68-0 record over three seasons at McClymonds High School, where Russell had played nearly a decade before, earning a scholarship to Creighton University. His brother, William, accompanied him to Omaha, but died of a heart attack while Silas was attending school.

Silas led the nation in rebounding as a junior, averaging 20.6 per game. In the 1964 NBA draft, St. Louis selected him 12th, or third in the second round.

Silas had a long career as an assistant and head coach after his NBA playing career, during which he averaged 9.4 points and 9.9 rebounds per game, played in two All-Star games, and was twice named first-team All-Defense.

He was a logical choice in 2003 to mentor the 19-year-old LeBron James in Cleveland as James, from nearby Akron, Ohio, made the transition from high school prodigy to the pros, having grown up during the NBA’s rough-and-tumble foundational era.

Silas became a tough-love enforcer in the carnival atmosphere that greeted James, barring James’s large entourage from practices and notifying official Cavs merchandise sellers that people other than the rookie phenom played for the team.

“Once LeBron steps foot here, he has to come with it like everyone else,” Silas told The New York Times in 2003.

Silas was fired in 2005 after the Cavaliers lost nine of their first twelve games, despite the fact that he and James appeared to form a strong bond, according to The New York Times.

“I admired Paul Silas a lot because he gave me a chance to show off my talent early on,” James told The New York Times. “Even after a loss, Coach was always upbeat.”

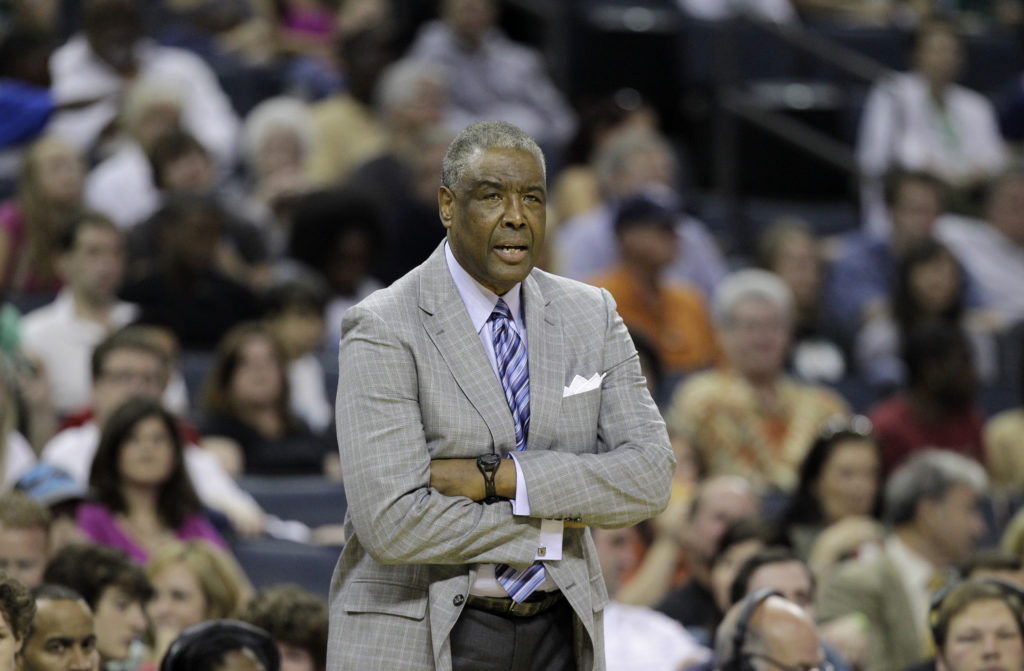

Silas coached the Charlotte Hornets to a 49-33 record in 1999.

The best of Silas’ 12 head-coaching seasons came in 1999-2000, when he led the Hornets to a 49-33 record. Bobby Phills, one of the team’s best players, died in a car accident with a teammate, David Wesley, during the season. Both were allegedly speeding near the team’s arena in their Porsches.

“The guys look at me as a father figure,” Silas, then 56, said as the Hornets mourned Phills while continuing their season, which ended in a first-round playoff loss.

Silas, who has expressed regret in interviews about his lack of a close relationship with his father, helped launch his son Stephen’s coaching career by hiring him to his Charlotte staff in 2000. In 2020, Stephen Silas was named head coach of the Houston Rockets.

Read also : Buffalo Bills’ Football game has been rescheduled after a player collapses on the field.

Silas is survived by his wife, Carolyn (Kemp) Silas, whom he married in 1966; a stepdaughter, Donna Turner, from Ms. Silas’s first marriage; three grandchildren; and two stepgrandchildren.

Silas embraced the reputation that had landed him the job as James’ mentor: that he was a resilient, cool-headed paternalistic figure.

In 1972, Silas told The Globe’s sports columnist Leigh Montville, “You can’t play this game mad — your own game just falls apart.” “I play fierce, but never mad.” There is a distinction.”